1.26 leadership, shamans and animism

We humans, linguistic beings, are the only species that can exchange individual ingenuity, ideas, skills and goods. We can consult each other in order to handle the challenges of our environment. Having started long ago as a tiny population of ape-men trying to survive in a hostile environment, thanks to this special faculty we now are the dominant vertebrates. This special faculty enabled our ancestors to survive in hostile environments and climates, and to survive big catastrophes that for many other species spelled extinction. It is this uniquely human faculty of being able to consult each other in order to make common decisions (democracy) that we will present as the base of a new, universal human self-confidence.

In the original groups of 25 individuals that existed at the time when our human nature was formed, during the long-long time of our Early Human ancestors, it may have been relatively easy to arrive at common decisions. In his 1990 book Our Kind. Who we are, where we came from & where we are going, Marvin Harris looks at today’s small populations: with 50 people per band or 150 per village. Everybody knows everybody else intimately, people are bound together in the reciprocal exchange of killed animals and gathered food.

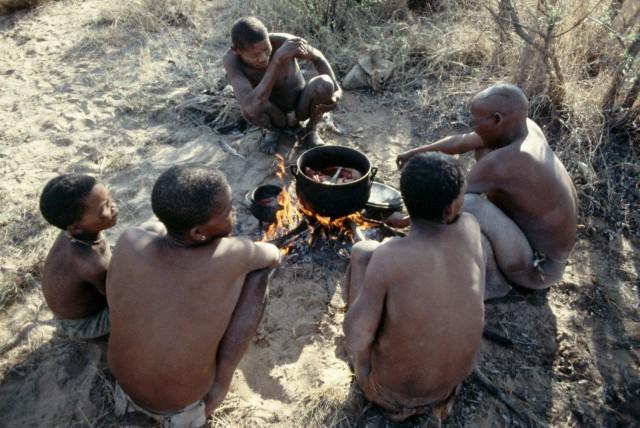

We, humanosophers, make a strong distinction between true GH-cultures (food gatherers) and AGR-cultures (food growers). Examples of the first are the Hadza (Tanzania), the Pygmies (Congo) and the !Kung People of Botswana (until the sixties still true hunter-gatherer cultures, as our prehistoric ancestors were millions of years long). Examples of the second, of the food growers (AGRs), are the Mehinacu of Brazil’s Xingu National Park or the Semai of Malaysia (both horticultural societies) and all later ‘wild tribes’ and farmers and cattle nomads, and still later ourselves, still being AGRs, still retaining traits of the ‘wild tribes’[1].

Since chance plays a great role in success of hunting and even in gathering, individuals who have a lucky catch one day, may need a handout on the next. So the best way to guarantee a daily portion of food is to be generous. Anthropologist Richard Gould said: “The greater the amount of risk, the greater the extent of sharing”. Richard Lee in The !Kung San (1979) watched small groups of men and women returning home every evening with the animals, wild fruits and plants that they had killed or gathered. They shared everything equally, even with camp mates who had stayed behind and spent the day sleeping or taking care of tools and weapons. “Not only families pool that day’s production, but the entire camp – residents and visitors alike – shares equally in the total quantity of food available. The evening meal of any one family is made up of portions of food from each of the other families. Foodstuffs are distributed raw or are prepared by the collectors and then distributed. There is a constant flow of nuts, berries, roots and melons from one family fireplace to another until each person resident has received an equal portion. The following morning a different combination of foragers moves out of the camp.”

What about leadership? In GH-societies leadership is unknown. To the extent that political leadership exists among simple AGR band-and-village societies, it is exercised by individuals called headmen. However, they lack the power to compel others to obey orders. How can such a headman lead? Among the Inuit, a group will follow an outstanding hunter, especially the leader of the whale hunting party.

But in all other matters, his opinion carries no more weight than any other man’s.

Among the Amazon Indians, headmanship is mostly an irksome job. As the first one to rise in the morning, the headman stands in the middle of the village and shouts, rousing his companions. If something needs to be done, it is the headman who works at it harder than anyone else. After a fishing or hunting expedition, he gives away more of the catch than anyone else. In trading with other groups, he is careful not to keep the best items for himself.

Among the Mehinacu the headman is a kind of scoutmaster. Among the warlike Yanomamö he is the captain at the raids. It is his task to patrol outside the shabono (village) in the morning and to risk being shot by a raiders group. He has also to maintain the biggest garden in order to feed guests (every man tries to keep his garden as small as possible!)

Among the Semai, who are horticulturists like the Amazon Indians and with a gift economy too, the headman is more a spokesman for public opinion than a molder of it. Disputes in the Semai community are resolved by holding a becharaa (public assembly) at the headman’s house. This assembly may last for days and involves thorough discussion of the causes, motivations and resolutions, ending with the headman charging either or both of the disputants not to repeat their behavior lest it endanger the community. Somebody who neglects the becharaa verdict, is really endangering his ife[2].

Gwi hunters in discussion; pay attention to the participating child

Gwi hunters in discussion; pay attention to the participating child

In hunter-gatherer societies, the principle of making decisions by reaching consensus of all adults in the group is the most frequent model of decision-making, although there are a few exceptions. The Gwi hunters in Botswana discuss their intentions carefully to avoid mutual interference.

Today most tribal AMM-groups, usually numbering some 150 people, are horticulturers living in an overpopulated region. Even when they live in peace and equality, in every social group nonconformists and malcontents try to use the system for their own advantage. Individuals who take more than they give and lay back in their hammocks while others do the work. But such freeloaders have to watch out for the shaman.

Hunter/gatherers such as the Hadza, the Kung San, the Pygmies, live in huts, built by the women on each campsite, and knew no headmen and no shaman, and are not animists. They live free and easy as GHs, singing the creation songs of their world.

Horticulturists however are AGRs, live in longhouses and shabonos, have an headman and a shaman. They know taboos and heavy initiation rituals. Every band- and village society has one or more shamans or witch-doctors with a special aptitude for communicating with the spiritual world and more specific: with the tribe’s god and other ghosts.

To go into trance they took hallucinogenic substances, danced to a monotonous drumbeat, inhaled magic smoke. For healing they have a rich repertoire of huffing, puffing and sucking practices, and multiple other tricks. This shaman, woman or man, is not the headman. In their spiritual world, illness or disease was not primarily physical, but rather caused by evil spirits. But from her or his divinatory trance, the shaman could pinpoint and accuse a freeloader, who might be lucky to be only expelled.

In all aspects that we will encounter in the following paragraphs about the transition from small populations to modern democracy we have to realize that our ancestors were AGRs, animistic creatures: believing that souls or spirits exist, not only in humans, but also in animals, trees, plants, rocks, mountains, rivers, the sea, the air and so on. People always believed – and some of us still believe – that these spirit beings can be induced or compelled to help us in hunting or winning a match, in healing from an illness or winning in the casino, in surviving a dangerous voyage or going to heaven.

For example, among the Inuit each man had to have a hunting song: a combination of chant, prayer and magic formula that he inherited from his father or his uncles. Around his neck he wore an amulet: a little bag filled with tiny animal carvings, bits of claws and fur, pebbles, insects, and other items, each corresponding to a personal spirit helper who protected him against hostile spirits and helped him to succeed.

(Real GHs such as our example Hadza, Pygmies and San, don’t know such ‘specialists’, and our prehistoric ancestors of the millions of years ago neither.)

Another human characteristic that stems from our ‘wild tribes’ past is tribalism: a strong feeling of identity with our parental tribe. As modern free market consumers, today we have learned to view ourselves primarily as individuals. But for a member of a tribe it is nearly impossible to feel what it means to be an individual. Being a tribal person means: being a member of one special family, and this family being part of one special clan. A broader loyalty may be felt for the special tribe to which that one clan belongs. That is what we have to keep in mind now we experience influx from non-western societies in our western societies.

An even wider loyalty can be felt in confrontation with a common, shared enemy: without such a shared enemy, our unity will disintegrate. For the Nazi ideology was its built-in antisemitism a ‘modern’ form of tribalism and our populists still try to awaken this feeling in us today.