Posts Tagged ‘group’

1.1 How it started

PART ONE: HOW HUMANS BECAME HUMANS FROM APES

Ten million years ago the climate became cooler and drier. Miocene jungles, that until then reached halfway into Eurasia, gradually retreated in the direction of the equator, being replaced by open savannahs. Five million years ago the jungle where our earliest ancestors lived in Northeast Africa, especially east of the Great Rift[1], started to undergo this change. It is here that our story begins.

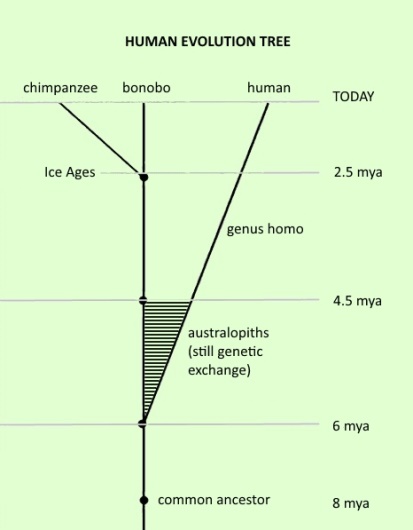

Humanosophic version of the human family tree

Humanosophic version of the human family tree

Our earliest ancestors were hominid apes. Frans de Waal (Bonobo 1997) says that, if we want an image of our earliest ancestors, we should look at the bonobos. They are the only kind of chimpanzee whose environment never changed. A species will only change when its environment changes. The environment of our earliest ancestors[2] changed totally, so our early ancestors changed totally. The environment of the chimpanzee ancestors changed much later and partially, so the chimpanzees changed partially.

Here, we will name our earliest ancestors ‘our[3] ancestor-bonobos’ (ANBOs).

It took millions of years for their jungle to turn into a savannah. Our ANBOs never were aware of this change; for them the world was in every phase like it always was. So the adaptations to the new conditions passed unnoticed. But for our story these adaptations are crucial. Not the physical adjustments so much, but especially the social and mental, in short the cultural evolution.

The savannah is a diverse environment consisting of open woodlands, mixed with impenetrable shrubs and grasslands accommodating herds of many kinds of grass eaters.

Our ANBOs lived in the woodlands, where like many present-day apes, they spent the nights in nests high in the trees. But these woodlands along the shores of rivers and lakes didn’t contain the fruit trees their ancestors used for sustenance. For food, our ANBOs had to roam the open grasslands: a dangerous area because of the big cats that preyed on the grass eaters. The saber-toothed tigers were specialists in preying on pachyderms: rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses and (ancestors of the) elephants.

I want to emphasize that the Miocene (22 – 5 million years ago) savannah was characterized by megafauna (large animals) and was much more dangerous than the current Serengeti. Lions, saber-toothed tigers and giant hyenas were formidable predators. Though the little ANBOs were much stronger than we are now, they needed special armament to roam the grasslands safely. This was: throwing stones to keep the predators on distance.

This can be illustrated by the behavior of apes today. Jane Goodall tells the story of the adult chimp male ‘Mister Worzle’. The bananas she left for the chimpanzees in order to study their behavior in the neighborhood, also allured baboons (large and brave monkeys) that frightened some female chimpanzees. But Mister Worzle did not give a centimeter of ground and threw anything he could grasp: grass, branches, once a bunch of bananas (baboons happy!). Soon he discovered that stones worked better and that bigger stones worked even better. And he began to gather them on a heap.

Our ANBOs needed to become ‘professional’ stone throwers. They could not take a step on the open grasslands in safety without their armament of stones. Who did throw men or women?

Women carried babies and had to gather food stuff. Men with their stones made sure that the group went safely around over the open grasslands. Division of tasks from the beginning .

One stone was not enough to ensure their safety; the men needed a handful of stones. But how you can as an ape carry a handful of stones?

skull sabre cat

skull sabre cat

Sabre cats – we already mentioned them – were specialists in predating fat-skins like elephant-like and rhinoceroses. They stalked such a meat fort and after a fierce sprint they turned open its soft underbelly (these cats could open their mouth unusually wide, the sabres laying in the extension of the skull (see photo). So they were not really ‘cats’.

Sabres ate only the entrails of their kill. The rest of the carcass was left to other animals. As soon as vultures started circling around from their high vantage point, lions and hyenas knew that a meal was coming. Lions were first, then the hyenas and the vultures ate the left-overs. Because of the steady supply of carcasses by the sabers the basically inedible, hairy or leathery skins and the skeletons stayed there. The ANBOs beat the bones for the marrow with their stones and used the hides to carry things[4]; with their long experience in braiding and wattling their sleep nests, tying these hides was easy.

But how will apes carry bags filled with stones? How do bonobos and chimps carry heavy things? They use their hands, so they must walk upright on their feet. Our ANBOs needed to become bipeds: without carrying some stones for armament, it would not be safe for them to venture into the open grasslands.[5] In tens of hundreds of thousands of years our ANBOs, having no other choice, turned into bipeds with longer and stronger legs, special pelvic and buttock muscles, special midriff and blood circulation[6]. At least they made a good start developing these properties, good enough for foraging on the savannah. They kept using their hands and feet for climbing: it was not safe to sleep on the floor, so they still needed them to make sleeping platforms high in the trees of the woodland.

Females had to carry their babies and gather food for themselves and the rest of the troupe, so they couldn’t carry and throw stones. Males couldn’t gather food: they had to offer protection, because hungry predators were always watchful for moments of unalertness. So our ANBOs cultivated a division of labor from the very beginning. Women and children gathered food: grass seeds, tubers and roots which they dug up with digging sticks[7], larvae and insects, eggs and small animals. The adult men did nothing but provide safety. The groups who practiced those behaviors most effectively, flourished (by keeping more young alive) and soon outnumbered the groups that were clumsier at these things. Through hundreds of generations, the population exhibiting these behaviors, were the fittest and survived.

The same mechanism applies to group harmony. Because of the big cats and the giant hyenas, the open savanna was a dangerous environment for apes and forced them to maintain strict group harmony. That was not a big problem at all: bonobos live in female-dominated groups characterized by group harmony, and solve tensions with sex.

Dentitions. Left: chimpanzee. Middle: australopith. Right: human

Clearly, our ANBOs probably ‘professionalized’ and optimized this behavior. The dentition of male bonobos still shows large canine teeth that can be used as weapons in sexual competition – although, chimpanzee canines are larger. Fossil australopith dentition shows reduced size of the canines: partially as a result of the need for grinding hard food like grass seeds, but also as a result of reduced male competition.[8] That our ANBOs solved all tensions with sex, is clear because while the size of the canines was reduced, the penises were enlarged! Of course the ‘attractive’ red vaginas of bonobo females and the heavy scrotums of bonobo males were not practical for bipeds, so those were reduced in size too. Every time the women were in estrus, this intensified male competition and group tensions. Therefore, the women’s periods became less noticeable as well. All these reductions were compensated with nice breasts and buttocks for the women, and continuous sexual willingness: mechanisms for reducing tensions and fostering group harmony.

Didn’t the men hunt? No way. Australopith bipedal locomotion was not fast enough to compete in hunting with the savannah predators. Nevertheless, besides birds eggs, insects and larvae there was yet another protein source for them on the savannah: hides.

Savannah today: more open space than in the ‘cradle of humanity’ which we suspect was in the Afar region of Ethiopia of 5 mya: woodland with less open spaces; but we can imagine an AP-group walking one after another between the grazers on their foraging trip. They were no danger to the grazers; as long as those kept quietly grazing, this meant for the ANBOs that it was safe for them as well, and they walked calmly, with their free hand occasionally stripping off grass seeds to chew them; in the meantime the women were searching for the edible tubers, recognizable by their leaves; and then the group had to stop for some time while the men watched with their stones.

Savannah today: more open space than in the ‘cradle of humanity’ which we suspect was in the Afar region of Ethiopia of 5 mya: woodland with less open spaces; but we can imagine an AP-group walking one after another between the grazers on their foraging trip. They were no danger to the grazers; as long as those kept quietly grazing, this meant for the ANBOs that it was safe for them as well, and they walked calmly, with their free hand occasionally stripping off grass seeds to chew them; in the meantime the women were searching for the edible tubers, recognizable by their leaves; and then the group had to stop for some time while the men watched with their stones.

As already mentioned, the hides all over the place, left behind as less edible by the other meat-eaters of the savannah, provided a new niche for the handy ANBOs. There was protein-rich tissue left on the hides to pick and scrape them with the sharp edges of bones, shells and stones. And when a hide was scraped totally clean, it made a perfect bag to carry things such as stones, or it made a blanket to use in cold nights, a screen against sun, wind, or rain. These multipurpose hides were the ANBOs’ first and only property. The paleos lack attention for the importance of the hides in the technical development of our ancestors, an omission that is understandable because hides are not preserved at archaeological sites (just like digging sticks and similar soft-material tools).

But philosophers are allowed to speculate more freely for the benefit of our Great Story, to immediately correct it as soon as a scientific evidence disproves a speculation[9].

Actually, this use of hides marked the beginning of ‘the stone age’: the beginning of the use of stone flakes for processing hides.

Processing hides, soon slaughter of found carcasses, later slaughter of the prey carcasses of the men: until recent HG-times it is females work. Turning stones into useful tools as scrapers and knives is females work. Our primatologists tell us that male chimpanzees use stones only for impressing behavior but female chimps use them for cracking hard nuts. Stone technology was a female invention, even before the birth of mankind.

All these environmental changes and physical adaptations developed unnoticed by our ANBOs. Just like all apes 7 million years ago, they made their daily foraging routes in a vast foraging territory. In the course of two million years, ever more open grasslands became part of their territory and daily route. All necessary adaptations developed during this time. By 5 million years ago, the hominins (australopiths, bipedal apes), including our future ANBOs, were experienced woodland/savannah foragers.

What remained rather unchanged was their way of life. They would leave their woodland nests early in the morning, wander along a route they knew perfectly, gathering food along the way, and finally arrive at the next woodland where they would share the gathered food and then make their nests high in the trees. The only part of the routine that changed, was that instead of eating their food while ranging on the grass lands, they carried most of the gathered food (tubers, grass seeds, larvae, eggs, and so on) to their overnight place in some wood, to be distributed equally among all group members. This was necessary because the men had less opportunity to get food enough during the foraging: their vigilance could not be allowed to weaken for a moment because of the permanent threat of the hungry predators.

After dinner and before the evening twilight, everybody had to climb in a tree and braid her or his nest.

Like their ancestors they lived in groups. Not too large: too much mouths to feed; not too small because there were enough men needed for the protection against predators. This asks for a number of around 25 individuals. But the composition of a group constantly changed and there was also constant exchange with nearby groups.

This meant that harmony within the groups as well as between the groups was conducive to the flourishing of the population. Therefore natural selection selected harmonious behavior as ‘good’. Our ancestors became ‘good natured’[10].

During 99.5 % of the long time span our species existed, our ancestors were first gatherer-scavengers and later gatherer-hunters.

- Paleo Tim White points to the Middle Awash (Ethiopia) as ‘the window on human past’ ↑

- Assuming that they lived in the forest of today’s Ethiopia, now desert but in the words of paleo Tim White at the time ‘a lush environment’ with lakes and rivers. ↑

- ‘our’ because bonobos and chimps have their ANBOs too ↑

- See also Nancy Tanner and Adrienne Zihlman in Mothers and Daughters of Invention (1995). ↑

- Other speculations about the origins of bipedalism, such as: better sight or less body parts exposed to the sun, lack the answer on the obvious question: why then didn’t the other savanna-dwellers like zebras or baboons become bipeds? ↑

- For the physical adaptations: Elaine Morgan Scars of evolution . London, 1990 ↑

- Today’s woodland chimpanzee females are observed digging up tubers with self-made digging sticks! ↑

- Mind also the reduction of the chewing apparatus from ape to human.↑

- After all, we did it thousands of years with Great Stories that were entirely dreamed up. ↑

- For Frans de Waal even chimpanzees are Good Natured (1979) ↑

1.7 the impact of fire control on communication

Most important was the impact of the campfire on communication. Before this forward momentum of fire control, communication was limited to daytime: during the foraging hours and the food sharing upon reaching the next sleeping place. Before twilight, for safety purposes, everyone had to climb high in a tree to make a nest, which effectively ended communication. But now, with a campfire keeping predators at bay, they could rest and communicate all night long! Those nightly hours could be used for nothing else but communication.

What did they communicate during this long nightly hours?

One might say: nothing at all, they just wrapped themselves in a hide and went to sleep while only one of them (a man of course) kept his eyes open and the fire burning. Speculating in this way however, one might easily overlook that they were a subspecies of bonobos: fervent communicators![1] In their new, more dangerous habitat they lived in closer togetherness than their rain forest ancestors, so they needed to be even more social. The new circumstances in combination with their bonobo-like inclination had already lead them to their new habit of names for the things.

So: what did they communicate? I propose it was the exchange of thoughts, expressions of what was going on in their mind: in other words, they were sharing emotions. For example the memory of some shocking event in the past day. Communicating these emotions took the form of performances. Let me dish up a possible ‘performance’ here.

The threatening encounter with the dangerous buffalo! The males had made a line with their stones at hand. The buffalo had hesitated, perhaps he remembered an encounter with a troupe of those apes, resulting in a hailstorm of painful stones. He scraped with his hoofs. After some long lasting seconds the buffalo had turned his back and moved.

Now, quietly around the campfire, a woman, with that threatening event in her mind, got up and imitated it with emotional gestures. The others screamed in approval. A man jumped up and imitated the buffalo. The emotional screaming increased. Other men jumped up and made the defense line, with imitated stones at hand. Then the ‘buffalo’ slunk off, and the screaming became jubilation. And calm returned in the group. But the nice performance stayed in everybody’s mind, and after several quiet minutes some women jumped up again and repeated the performance. And again, and again, until everybody wrapped himself in his hide to go to sleep. Evening after evening they did ‘the buffalo’ over and over, until a new event was subject of a new performance.

Generations after generations similar nightly performances became ever more sophisticated, and the gestured communication too. Sophistication means that the gestured ‘words’ underwent standardizing and shortening. Because when the beginning of a gestured ‘word’ is already understood, you don’t need to finish the whole gesture. In a group of women gossiping by sign language and cries, each woman wants to contribute her share. (Why women? Hunting men make no noise. But gathering women chatter and laugh: noise chases serpents away.)

Expressing such emotional thoughts the person used her/his whole body (just like bonobos do today) with accompanying cries. The others responded with imitating gestures and cries, and many of them jumped up and joined the communicating person. And when communicating very emotional items, the whole group was dancing and crying, over and over. From generation to generation, this behavior became ever more ritualized, controlled and refined.

When we say ‘ritualizing’, we mean, as neatly formulated in Wikipedia, “behavior that is formally organized into repeatable patterns, the basic function of which is to facilitate interactions between individuals, between an individual and his deity, or between an individual and himself across a span of time.” Ritual synchronizes the activity of participants, a phenomenon that contributes to group cohesion – which can also contribute to survival. Some scholars also suggest that human ritual behavior reduces anxiety. It makes me think of the ‘war dances’ of the Yanomamö[2] , as preparation of a raid. A more modern example may be the ritual drilling of recruits in the barracks.

They began dancing and singing around the campfire. In my view, dancing and singing cannot be separated here, which why we may call it dancing/singing.

- We can pass a fruit tree without noticing the chimpanzee group we were looking for, as it sits silently in the canopy. On the other hand, a group of bonobos will be heard from a far distance, screeching like a mob of barking dogs. See Frans de Waal’s book Bonobo (1997) and Craig Stanford’s book Significant Others (NY 2001)

↑ - Napoleon Chagnon Yanomamö. The Fierce People (New York, 1983)

↑

1.23 three steps into machism

Hunter-gatherer bands, stumbled in overpopulation-situation, in which the males have become warriors and aware of their importance for the survival of the band, take over the ancestral female dominance. That is the beginning of male dominance. The second step into machism is that men decide to build a men’s initiation house, somewhere in the forest or in a deep cave wideness, separating young boys from their mothers and from the world of women, stealing the holy flutes and other paraphernalia, and start their own male initiation ceremonies. The third step is institutional violence against women. This occurs only in the fiercest tribal warfare. In all tribal societies all over the world we see one of those three gradations of male dominance.

Chimpanzees are examples of how an overpopulation-situation, causing warfare between competing groups, also contributed to male dominance. But can we observe machism in our relatives, the chimpanzees? No. Among chimpanzees, dominant alpha males do need the support of women. As soon as this support fails, they lose their dominance.

From the very beginning of our species, defense was a male business. Males took care of the defense against big cats and hyenas, enabling woman and children to gather the food in safety. But while in itself this defensive task may have led to male dominance in overpopulation situation, it is not something that automatically also produces machism.

What made human males into machists? This is an important issue, because since the advent of overpopulation until modern times women have suffered from male violence and aggression, against our innate GH-nature. It is only recently (in our Western consumer societies) that women have begun to regain their ancestral high status. So what may be the historical root of machism in humans?[1]

As a general hypothesis, we may suppose that machism is characteristic for some horticulturalist tribes that live in overpopulation stress all over the world, but not for all of those. First, an example of a group where male dominance has been established, but without machism. An example are the Amazonian Xavante, described by anthropologist David Maybury-Lewis. The Xavante have chiefs, have extensive boys initiation ceremonies, but without violence against women. Because the Xavante live in relative peaceful coexistence with their neighbors, so not in permanent stress.

As an example of a band where not just male dominance, but also machism emerged, we propose another Amazonian band: the Yanomamö, described by Napoleon Chagnon. Their groups live in permanent threat of warfare. Chagnon observed[2] that young boys and girls are treated differently: the girls have to help their mothers at early age and spend a great deal of time working, while the boys spend their childhood playing with other boys. The boys are also encouraged to be fierce. When a toddler slaps his father in the face, father is glad and encourages his child to slap harder. From early childhood they see their mothers and sisters beaten up by their fathers and other men, for the slightest omissions. Even his mother encourages the young boy when he inflicts a blow on his sister. The boys are quick to learn their favored position with respect to girls.

[Note that this is characteristic of all the wild tribes, including the Arab, and thus for Muslims and many other not-western cultures. Even Western societies have not yet transcended the ‘tribal tribes’ stage. See Donald Trump: the example of stage I and II of our human nature par excellence. Civilization progresses painfully slowly.]

How can this cultural attitude have emerged in an ancestral egalitarian GH-society with female high status? Because an overpopulated world brought new situations, where for the first time women found their food sources plundered by intruders. In such a situation, they wanted fierce men to defend their food sources from stealing intruders. As overpopulation progressed, women also wanted fierce men to protect them against raiders who might abduct women who were collecting fire wood or garden produce. In such a hostile overpopulation-world, the ‘fittest’ groups are the groups with the most violent males.

Therefore, in these groups women will see violence as a good quality in males and promote this warrior-attitude in their men and sons.

It is because of the constant threat of being attacked by a hostile group that the Yanomamö have lost their traditional initiation rituals and religious festivals, and have serious problems with male youth.

The Xavante are not involved in warfare and still have their initiation rituals, age groups, songs and dances.

The Xavante are not involved in warfare and still have their initiation rituals, age groups, songs and dances.

By advancing colonist plantations their habitat is so shrunken that they have ceased to be nomadic and live in horseshoe villages on the open savanna. But still women build the ‘beehive’ houses and collect the food, while men hunt tapir and deer, and plant crops (maize, beans, pumpkins) in shifting cultivation.

They have no problems with male youth because of their strict and hard young initiation period. And by the eight age groups in which the men live their lives every five years to their old age.

- First of all: is it not a pure AGR-characteristic. Some Australian aboriginal groups know machism, while on the other hand the continent traditionally did not provide the basic condition for agriculture (grains, fruits or vegetables that can be conserved until the next year). Agriculture was imported only recently, by English colonists. So by tradition, all 263 Aboriginal tribes are GHs. ↑

- 67 The Fierce People (1983), chapter 4 ↑

- First of all: is it not a pure AGR-characteristic. Some Australian aboriginal groups know machism, while on the other hand the continent traditionally did not provide the basic condition for agriculture (grains, fruits or vegetables that can be conserved until the next year). Agriculture was imported only recently, by English colonists. So by tradition, all 263 Aboriginal tribes are GHs. ↑

- 67 The Fierce People (1983), chapter 4 ↑

- David Maybury-Lewis Millennium (New York, 1992)