Archive for September, 2018

1.1 How it started

PART ONE: HOW HUMANS BECAME HUMANS FROM APES

Ten million years ago the climate became cooler and drier. Miocene jungles, that until then reached halfway into Eurasia, gradually retreated in the direction of the equator, being replaced by open savannahs. Five million years ago the jungle where our earliest ancestors lived in Northeast Africa, especially east of the Great Rift[1], started to undergo this change. It is here that our story begins.

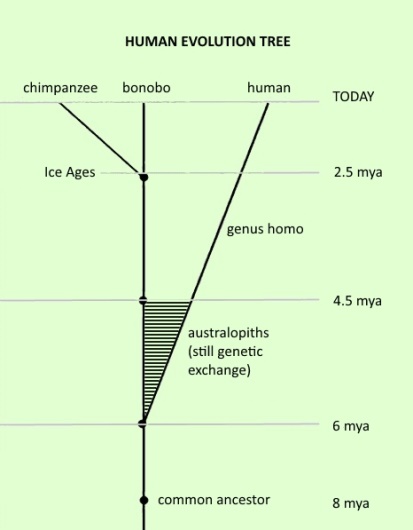

Humanosophic version of the human family tree

Humanosophic version of the human family tree

Our earliest ancestors were hominid apes. Frans de Waal (Bonobo 1997) says that, if we want an image of our earliest ancestors, we should look at the bonobos. They are the only kind of chimpanzee whose environment never changed. A species will only change when its environment changes. The environment of our earliest ancestors[2] changed totally, so our early ancestors changed totally. The environment of the chimpanzee ancestors changed much later and partially, so the chimpanzees changed partially.

Here, we will name our earliest ancestors ‘our[3] ancestor-bonobos’ (ANBOs).

It took millions of years for their jungle to turn into a savannah. Our ANBOs never were aware of this change; for them the world was in every phase like it always was. So the adaptations to the new conditions passed unnoticed. But for our story these adaptations are crucial. Not the physical adjustments so much, but especially the social and mental, in short the cultural evolution.

The savannah is a diverse environment consisting of open woodlands, mixed with impenetrable shrubs and grasslands accommodating herds of many kinds of grass eaters.

Our ANBOs lived in the woodlands, where like many present-day apes, they spent the nights in nests high in the trees. But these woodlands along the shores of rivers and lakes didn’t contain the fruit trees their ancestors used for sustenance. For food, our ANBOs had to roam the open grasslands: a dangerous area because of the big cats that preyed on the grass eaters. The saber-toothed tigers were specialists in preying on pachyderms: rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses and (ancestors of the) elephants.

I want to emphasize that the Miocene (22 – 5 million years ago) savannah was characterized by megafauna (large animals) and was much more dangerous than the current Serengeti. Lions, saber-toothed tigers and giant hyenas were formidable predators. Though the little ANBOs were much stronger than we are now, they needed special armament to roam the grasslands safely. This was: throwing stones to keep the predators on distance.

This can be illustrated by the behavior of apes today. Jane Goodall tells the story of the adult chimp male ‘Mister Worzle’. The bananas she left for the chimpanzees in order to study their behavior in the neighborhood, also allured baboons (large and brave monkeys) that frightened some female chimpanzees. But Mister Worzle did not give a centimeter of ground and threw anything he could grasp: grass, branches, once a bunch of bananas (baboons happy!). Soon he discovered that stones worked better and that bigger stones worked even better. And he began to gather them on a heap.

Our ANBOs needed to become ‘professional’ stone throwers. They could not take a step on the open grasslands in safety without their armament of stones. Who did throw men or women?

Women carried babies and had to gather food stuff. Men with their stones made sure that the group went safely around over the open grasslands. Division of tasks from the beginning .

One stone was not enough to ensure their safety; the men needed a handful of stones. But how you can as an ape carry a handful of stones?

skull sabre cat

skull sabre cat

Sabre cats – we already mentioned them – were specialists in predating fat-skins like elephant-like and rhinoceroses. They stalked such a meat fort and after a fierce sprint they turned open its soft underbelly (these cats could open their mouth unusually wide, the sabres laying in the extension of the skull (see photo). So they were not really ‘cats’.

Sabres ate only the entrails of their kill. The rest of the carcass was left to other animals. As soon as vultures started circling around from their high vantage point, lions and hyenas knew that a meal was coming. Lions were first, then the hyenas and the vultures ate the left-overs. Because of the steady supply of carcasses by the sabers the basically inedible, hairy or leathery skins and the skeletons stayed there. The ANBOs beat the bones for the marrow with their stones and used the hides to carry things[4]; with their long experience in braiding and wattling their sleep nests, tying these hides was easy.

But how will apes carry bags filled with stones? How do bonobos and chimps carry heavy things? They use their hands, so they must walk upright on their feet. Our ANBOs needed to become bipeds: without carrying some stones for armament, it would not be safe for them to venture into the open grasslands.[5] In tens of hundreds of thousands of years our ANBOs, having no other choice, turned into bipeds with longer and stronger legs, special pelvic and buttock muscles, special midriff and blood circulation[6]. At least they made a good start developing these properties, good enough for foraging on the savannah. They kept using their hands and feet for climbing: it was not safe to sleep on the floor, so they still needed them to make sleeping platforms high in the trees of the woodland.

Females had to carry their babies and gather food for themselves and the rest of the troupe, so they couldn’t carry and throw stones. Males couldn’t gather food: they had to offer protection, because hungry predators were always watchful for moments of unalertness. So our ANBOs cultivated a division of labor from the very beginning. Women and children gathered food: grass seeds, tubers and roots which they dug up with digging sticks[7], larvae and insects, eggs and small animals. The adult men did nothing but provide safety. The groups who practiced those behaviors most effectively, flourished (by keeping more young alive) and soon outnumbered the groups that were clumsier at these things. Through hundreds of generations, the population exhibiting these behaviors, were the fittest and survived.

The same mechanism applies to group harmony. Because of the big cats and the giant hyenas, the open savanna was a dangerous environment for apes and forced them to maintain strict group harmony. That was not a big problem at all: bonobos live in female-dominated groups characterized by group harmony, and solve tensions with sex.

Dentitions. Left: chimpanzee. Middle: australopith. Right: human

Clearly, our ANBOs probably ‘professionalized’ and optimized this behavior. The dentition of male bonobos still shows large canine teeth that can be used as weapons in sexual competition – although, chimpanzee canines are larger. Fossil australopith dentition shows reduced size of the canines: partially as a result of the need for grinding hard food like grass seeds, but also as a result of reduced male competition.[8] That our ANBOs solved all tensions with sex, is clear because while the size of the canines was reduced, the penises were enlarged! Of course the ‘attractive’ red vaginas of bonobo females and the heavy scrotums of bonobo males were not practical for bipeds, so those were reduced in size too. Every time the women were in estrus, this intensified male competition and group tensions. Therefore, the women’s periods became less noticeable as well. All these reductions were compensated with nice breasts and buttocks for the women, and continuous sexual willingness: mechanisms for reducing tensions and fostering group harmony.

Didn’t the men hunt? No way. Australopith bipedal locomotion was not fast enough to compete in hunting with the savannah predators. Nevertheless, besides birds eggs, insects and larvae there was yet another protein source for them on the savannah: hides.

Savannah today: more open space than in the ‘cradle of humanity’ which we suspect was in the Afar region of Ethiopia of 5 mya: woodland with less open spaces; but we can imagine an AP-group walking one after another between the grazers on their foraging trip. They were no danger to the grazers; as long as those kept quietly grazing, this meant for the ANBOs that it was safe for them as well, and they walked calmly, with their free hand occasionally stripping off grass seeds to chew them; in the meantime the women were searching for the edible tubers, recognizable by their leaves; and then the group had to stop for some time while the men watched with their stones.

Savannah today: more open space than in the ‘cradle of humanity’ which we suspect was in the Afar region of Ethiopia of 5 mya: woodland with less open spaces; but we can imagine an AP-group walking one after another between the grazers on their foraging trip. They were no danger to the grazers; as long as those kept quietly grazing, this meant for the ANBOs that it was safe for them as well, and they walked calmly, with their free hand occasionally stripping off grass seeds to chew them; in the meantime the women were searching for the edible tubers, recognizable by their leaves; and then the group had to stop for some time while the men watched with their stones.

As already mentioned, the hides all over the place, left behind as less edible by the other meat-eaters of the savannah, provided a new niche for the handy ANBOs. There was protein-rich tissue left on the hides to pick and scrape them with the sharp edges of bones, shells and stones. And when a hide was scraped totally clean, it made a perfect bag to carry things such as stones, or it made a blanket to use in cold nights, a screen against sun, wind, or rain. These multipurpose hides were the ANBOs’ first and only property. The paleos lack attention for the importance of the hides in the technical development of our ancestors, an omission that is understandable because hides are not preserved at archaeological sites (just like digging sticks and similar soft-material tools).

But philosophers are allowed to speculate more freely for the benefit of our Great Story, to immediately correct it as soon as a scientific evidence disproves a speculation[9].

Actually, this use of hides marked the beginning of ‘the stone age’: the beginning of the use of stone flakes for processing hides.

Processing hides, soon slaughter of found carcasses, later slaughter of the prey carcasses of the men: until recent HG-times it is females work. Turning stones into useful tools as scrapers and knives is females work. Our primatologists tell us that male chimpanzees use stones only for impressing behavior but female chimps use them for cracking hard nuts. Stone technology was a female invention, even before the birth of mankind.

All these environmental changes and physical adaptations developed unnoticed by our ANBOs. Just like all apes 7 million years ago, they made their daily foraging routes in a vast foraging territory. In the course of two million years, ever more open grasslands became part of their territory and daily route. All necessary adaptations developed during this time. By 5 million years ago, the hominins (australopiths, bipedal apes), including our future ANBOs, were experienced woodland/savannah foragers.

What remained rather unchanged was their way of life. They would leave their woodland nests early in the morning, wander along a route they knew perfectly, gathering food along the way, and finally arrive at the next woodland where they would share the gathered food and then make their nests high in the trees. The only part of the routine that changed, was that instead of eating their food while ranging on the grass lands, they carried most of the gathered food (tubers, grass seeds, larvae, eggs, and so on) to their overnight place in some wood, to be distributed equally among all group members. This was necessary because the men had less opportunity to get food enough during the foraging: their vigilance could not be allowed to weaken for a moment because of the permanent threat of the hungry predators.

After dinner and before the evening twilight, everybody had to climb in a tree and braid her or his nest.

Like their ancestors they lived in groups. Not too large: too much mouths to feed; not too small because there were enough men needed for the protection against predators. This asks for a number of around 25 individuals. But the composition of a group constantly changed and there was also constant exchange with nearby groups.

This meant that harmony within the groups as well as between the groups was conducive to the flourishing of the population. Therefore natural selection selected harmonious behavior as ‘good’. Our ancestors became ‘good natured’[10].

During 99.5 % of the long time span our species existed, our ancestors were first gatherer-scavengers and later gatherer-hunters.

- Paleo Tim White points to the Middle Awash (Ethiopia) as ‘the window on human past’ ↑

- Assuming that they lived in the forest of today’s Ethiopia, now desert but in the words of paleo Tim White at the time ‘a lush environment’ with lakes and rivers. ↑

- ‘our’ because bonobos and chimps have their ANBOs too ↑

- See also Nancy Tanner and Adrienne Zihlman in Mothers and Daughters of Invention (1995). ↑

- Other speculations about the origins of bipedalism, such as: better sight or less body parts exposed to the sun, lack the answer on the obvious question: why then didn’t the other savanna-dwellers like zebras or baboons become bipeds? ↑

- For the physical adaptations: Elaine Morgan Scars of evolution . London, 1990 ↑

- Today’s woodland chimpanzee females are observed digging up tubers with self-made digging sticks! ↑

- Mind also the reduction of the chewing apparatus from ape to human.↑

- After all, we did it thousands of years with Great Stories that were entirely dreamed up. ↑

- For Frans de Waal even chimpanzees are Good Natured (1979) ↑

1.2 Names for things

So far, the ANBOs didn’t stand out from other australopith species, such as afarensis or africanus, whose remnants our paleos have found in Africa. Now we get to the incidental invention that led, in the end, to our human condition.

For us, what we are going to tell now has been a familiar story for decennia. But yesterday (June 11, 2018) we read the article by Richard Nordquist[1] on ThoughtCo and again we knew that for philosophers in general and for linguists in particular it is still new. He quotes Bernard Campbell[2]”We simply do not know, and never will, how or when language began”, and continues with the enumeration of the five most common theories which nevertheless have been put forward to then pull all five down. He ends by citing Christine Kenneally[3] “To find out how language began is the hardest problem in science today.”

Certainly, discipline scientists have to limit themselves to hard facts and the first words have left no trace. But reconstructing our Genesis story is philosophical work and for humanosophers, making use of as much discipline as possible is sufficient. Moreover, the astronomers leave with their Big Bang from an unproven just-so-story, in order to explain their universe phenomena satisfactorily. So we consider ourselves entitled with ours.

Again a women’s invention. No invention that resulted from a change in their environment, no new form of adaptation. Today there are chimpanzee women in Ugalla (Tanzania) who leave the protection of the woodland during the wet seasons to excavate tubers on the open grasslands with homemade digging sticks. For us the proof that our ANBOs did fine without any linguisticness. We would today still be ape-men (so normal animals) somewhere in Africa, if not 5 mya had happened something accidental in one of the ANBO groups.

But where something is possible, it happens too, sooner or later. So it was bound to happen somewhere and sometime in the australopitic world, that in one group, presumably in a forwarded group, and probably again a woman, somebody started with the first name for a thing. Because we are a symbolic species now and no other species has names for the things – if there was another species with names for things, then we would have noticed this for a long time. Because disposing of names for the things does something with an animal. It does 5 things and later on we will list these 5 things.

Of course there were forwarded and backwarded living-groups, and different environments. In forwarded groups, in more savanna-like environment such as the Rift valley around 5 millions of years ago (mya), one may imagine that in the early mornings a patrol of three adult men scouted the route that the alpha woman had in mind for the next foraging trip. So that not the whole group of old people and children had to go back and decide to another route if some danger had been identified. In this case the patrol returned and imitated [sabre tiger!] or [hyenas!]. [ 4]

Our speculation is – and if you can imagine a better one, you are welcome – that on one morning a young girl of such a vicious group was very happy because she knew that the group would come across bushes with tasty berries on the foraging route of that day. Her two girlfriends looked at her in astonishment: why was this euphoria? The girl racked her brain: how could she communicate what she had in her mind?

I made a painting of this pivotal moment: the birth of humanity

Inspired by the gestured imitations of the morning scouts she imitated [berry], [picking], [putting in mouth’], facial expression of delicious tasting and finally pointing with her digging stick in the direction of the group, already being on its foraging way.

No understanding. Another time. And another time. One girl became impatient: it was dangerous to detach the protection of the group. The older girlfriend racked her brain: and after again the berry-pick-imitation the penny dropped at her. Yess!!

The girls ran after the group, laughing, and they had fun with the berry-pick pantomime the whole day. Some women understood the imitation and also got fun.

The next morning the older girl friend invented something the group might encounter that day: digging tubers! And she imitated for her friends [digging] [corms]. And again fun with the new imitation, and some more women joined the fun of the imitation.

Except that the game was fun, it was also useful: so women could communicate what they had in mind. It was an extension but also an enrichment of their normal group animal communication. It improved their cooperation, benefited survival, and the group flourished more than australopithic groups without this handy practice. When young women moved to a neighboring group to find a mate, they took this habit along, spreading this gesturing practice over the whole clan and tribe. Our ancestors! Our ANBOs.

This was an incidental, casual beginning of a new group culture. It must have been contingent, because it was not necessary for surviving.[5] The childish game might have been forgotten, in which case we would be still a kind of ape men in the African savanna today. But this new ‘culture’ turned out to be helpful and useful. It improved group cooperation.

Keep in mind that in our opinion this has been the second women’s invention that has made us from apes into people. Why a female again (after stone technology)? Because most (if not all) new things in apes begin with young females[6].

You may notice that it was the men of the patrols after all? No, because their imitations were no more than the delayed warning cries of the vervet monkeys: stimulus-response reactions.

An incidental new habit … a huge step towards becoming human! This was a totally new phenomenon in the history of life on earth. All group animals have their own means of communication. But in no other species individuals can communicate about something beyond their awareness, about something in another place, in another season, in the past or in the future. These gesture-imitations of things by our ANBOs were (the beginnings of) names for things, enabling them to communicate on a new level.

A new level?

Disposing of names for things does something with an animal. It does 5 things, and you can better memorize these 5 things if you want to know what had made our species so special in the animal world. I will briefly list them here, and I will repeat them in more detail in the following section, so that they have a better chance of ending up in your memory.

- A name IS not the thing . With the enrichment of their communication with names for things, a sense of distance developed between the appointing ANBOs and the appointed environment. The ANBOs became emotionally ‘detached’ from their environment, while the other animals remained unwillingly part of it.

- With the name you ‘grasp’ the thing (or action, whatever). The ANBOs began to “grasp” their environment. She entered the path of ever better understanding things. We are still on that path today.

- “Grabbing” things by name gives a sense of power over things. With the name of the saber-toothed tiger the ANBO got a feeling of power over the dreaded monster. It was this mechanism that caused the ANBOs to use the fire that their fellow animals continued to flee from.

- You know the thing with the name of the thing. Knowledge acquired in one generation could be transferred to the next. Knowledge could accumulate at our ANBOs.

- Individual intelligence could be thrown in a heap, the ANBOs could brainstorm. They could forge plans. Together with their fire, they developed from frightened apemen to the hooligans of the savannah.

Notes

1.”Five Theories on the Origins of Language”

2. author of “Humankind Emerging”, 9the ed. 2018

3. “The First Word: Search for the Origins of Language”, 2007

4. or a male buffalo …

5. PNAS, December 4, 2007: “Savannah chimpanzees use tools to harvest underground storage organs of plants” Recent addition: To our surprise, the scientific research of the Australian research group led by Prof. Fay (Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 9 March 2022) confirmed our HINTS speculation!

6. For instance, the young macaque IMO on the Japanese island Koshima who started with washing her sweet potatos in 1953, a ‘culture’ that is still in use long after her dead

1.3 The 5 things that made our species so special in the animal world

- A name for a thing is not the thing. There is an unbridgeable mental gap between the thing and the name (symbol, word, image) of it. The

French painter dedicated a painting to this phenomenon in 1922: Ceci nést pas une pipe. Going to live with an enrichment of our normal group animal communication with names for things has brought our species into a world of words, a spiritual (or ‘virtual) world of named things. This phenomenon has already occupied our philosophers from Plato.

French painter dedicated a painting to this phenomenon in 1922: Ceci nést pas une pipe. Going to live with an enrichment of our normal group animal communication with names for things has brought our species into a world of words, a spiritual (or ‘virtual) world of named things. This phenomenon has already occupied our philosophers from Plato.

It creates a feeling of distance between the namer and the named thing: the ‘mental gap’, the human condition.

In other words: it creates a distance between the subject (the namer) and the object (the named thing): we are distant from our environment, while normal animals willlessly remain part of it. - With a name you grab the thing. You can see the name (word, symbol, image) as a handle on the thing with which you can ‘grasp’ it, get a ‘grip’ on it. You can grab the idea (the mental thing) with it and reach it out to the other person who can grasp it and gets the same idea in her mind immediately.

With names for things our ANBOs entered the path of ‘grasping’ (understanding) the things of their world and we are still on this path of ever better understanding the things. - With the name for the saber-toothed tiger the ANBOs got mental ‘grip’ on the monster and it reduced their instinctive fear a little.

Conversely, this also means an impairment of the named. In wild tribes one may never name an adult: one needs to describe someone (such as: father of …). Jews (being from a wild tribe culture) are not allowed to call their god by name. Muslims (being from a wild tribe culture) are not allowed to depict their founder Mohammed.

With names for things ANBOs got emotional power over things. This led them to use the fire instead of keeping to flee for it like all other animals. [1] - With names for things ANBOs could transfer knowledge acquired in one generation to the next. Knowledge could accumulate.

- Two know more than one, and with the whole group ANBOs could brainstorm, could solve big problems, could devise plans. Together with their fire the ANBOs changed from fearful troops of ape-men to the ‘hooligans of the savannah’.

As a result of these five effects of disposing of names for things our ancestor-australopiths developed more flexibility and inventiveness than other animals and even than other australopiths. Australopith groups without this facility of conferring with each another – boisei, robustus, aethiopicus, even afarensis– died out, presumably with some help of the ancestor-australopiths, the ‘hooligans’ of the Pliocene savannah.

Darwinian biologist and philosopher Richard Dawkins has introduced the concept meme as the cultural twin of the biological gen. Just like genes ensure transfer of physical properties, memes (ideas, melodies, fashions, techniques, practices) ensure transfer of cultural elements. It is important to note here that the names for things we are talking about, constitute a concept on a more fundamental level than Dawkin’s memes. In a way, this name thing – the linguistic capacity – is a condition that is necessary for, and at the root of, the development of cultural memes.

- with the exception of pets and … birds ↑

1.12 linguisticness and its consequences

The philosophical term ‘linguisticness’ is the translation of Heidegger’s concept Sprachlichkeit. In the work of another hermeneutic philosopher it appears even as ‘linguisticality’[1], but for humanosophic purposes the word ‘linguisticness’ suffices. However, our definition is not exactly the same as Heidegger’s.

In the humanist/philosophical view on human nature linguisticness is the mental condition of an ape who has begun to use names for the things, gradually finding himself in a named world, in a virtual ‘words-world’. The definition of linguisticness in this context (in another sense than just ‘the ability to use language’) is obvious: with ‘linguisticness’ we mean the mental predisposition to experience the world in concepts. This is the characteristic that makes us humans unique among all animals.

Our linguistic consciousness, the grasping, comprehending understanding of the world, started with the first gestured name (‘the first word’[2]).

In the beginning, communicating with names for the things – and also thinking with it – was still rather inadequate.

Nevertheless, eventually the humans had to rely on it: they had to make instinct secondary (no two captains on the ship of your decision making). And when you no longer use an organ it will shrink. Something similar may have been happen to our instinct.

Because the humans began to understand their world with a linguistic understanding that was still weak and unreliable, they fell prey to incertitude.

Itis a major consequence of linguisticness: it made us into ‘worrying apes’.

By itself, incertitude is not a new phenomenon in the animal world. When an animal comes upon a situation where his instinct cannot give an adequate impulse, it may feel uncertain. But for humans, incertitude became a more permanent part of daily life experience.

One cannot live with constant incertitude, so the early humans developed two anguish allaying mechanisms:

repetition and believing.

– Repetition: rhythm, dancing, singing, rituals: I already mentioned some scholars who suggest that human ritual behavior reduces anxiety. Tradition has the same effect: doing things the same way they had be done since many generations. Consequently, the early humans were astonishingly conservative. Especially the females: the most real humans.

Over more than a million of years, the form and material of their hand-axes (female tool) showed virtually no change. In their named world, the most important tradition and ritual was the danced singing of the creation story (females were leading in religion[3]) every night around the camp fire.

– Believing: a firm inner conviction that things are the way we want them to be, or at least are the way somebody with status and/or authority says they should be.

Until our scientific times, it was never important whether a story was true. It mattered only if it was a good (useful) story, a story which people wanted to be true, which was felt to be relevant to their existence. Just like in a later era, in the time of patriarchal society, the story of the birth of Eve out of a rib of Adam became a good story because it was just what the men wanted to hear, as a reinforcement of their supremacy. Such stories had to be true.

In primitive times humans were not yet acquainted with the concept of authority: in the group, they were strictly equal. Therefore the most important parts of their belief were not based on some kind of authority, but rather on magic (fear allaying ritual actions) and myth (tradition-based elucidations of the world).

The thus acquired certitude enabled our ancestors to intervene in their environment.

As I said before: names for the things also gave them (a feeling of) power over the things. Linguisticness created a distance between the understanding brain and the object (the understood thing or phenomenon). Humankind became a factor in nature that mastered a mental but also an instrumental power over the world.

The first critical intervention in the natural environment being the control of fire.

The inner conviction that some ritual words – such as incantations, charms or spells – evoke magical forces that can create or destroy, is just as ancient. Knowing somebody’s name gives a feeling of power over him. Naming somebody can be felt as disrespectful, or even be understood as violating the named one’s integrity.

This is why in several traditional religions,the actual name of the feared powers (be it natural elements such as a tiger or a volcano, or the gods) may not be spoken aloud. In Judaism, the god has to be circomscribed.

As another consequence of having names for the things, the ability to exchange complex thought scenarios with each other became a powerful new strategy: two know more than one, and people now could share their thoughts and overcome the biggest problems. Essentially, this is the power of democracy.

Some other consequences need to be mentioned here. Between the linguistic beings and their environment, an apparatus of thousands of concepts (the sign language codes associated with representations in the brains) arose, which created a ‘virtual’ world.

All things in our world are named things (things only exist as far as we have a name for it), but how can we know if there are no things that we do not (yet) have a name for?

Many philosophers (Plato with his cave metaphor; Kant with the thing as representation and the thing in itself) wrestled with the feeling that, besides the world we know, there is a another or even more real world, but one which slips out of our hands as soon as we try to name and know it. Talking about it is by definition not possible.

Perhaps this philosophical ‘second’ or ‘real’ world exists in the larger part of our thinking as the unconscious : linguistic consciousness seems to take only 20% of our actual thinking.

A last important consequence was the emergence of the bastion of holiness.

Our ancestors kept their incertitude at bay with belief and magic rituals. They believed when and where they couldn’t know for sure: these beliefs were imagined certitudes, pseudo-elucidations, not based on hard evidence. Deep in their minds, incertitude lived on. So the necessary elucidations were canonized into holy elucidations.

Holy is unassailable, untouchable: something holy may not be doubted or called in question. But this runs counter to the progress of our linguistic consciousness, our knowing, our rationality. To the path of ever better grasping (understanding) things. To the only ability which can really free us from incertitude. So please stop with declaring thins holy.

Fortunately, we now live in the time of free market economy. It frees us out of the bastion of holiness. It is a blessing for mankind.

Unfortunately, since neoliberalism in the 1980s entered the free marked economy, it got the bad dog of the finance capital biting on its leg. We have to struggle the bad dog back to the chain of government.

Maybe the humanosophic project as developed in Part Two could help.

1.13 religion explained

Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought is the title of a 2001 book of Pascal Boyer, a French-American anthropologist. Because of its actuality and its daring title it is a much discussed and translated book. Most of the reviews, however, are not very enthusiast, complaining of its dry and abstract philosophical and cognitive-psychological argumentation. Even more serious is the conclusion that the book does not really explain the phenomenon of religion. Boyer himself excuses this lack of satisfactory explanation with the statement that “religion is not a single entity resulting from a single cause.”[1]

But is he right? Couldn’t religion in essence be just that: a single entity resulting from a single cause? For the humanosopher, who explains consciousness as linguistic consciousness, the obvious mission here is to unravel the real evolutionary origin of religious thought.

Our ancestors, now armed not only with stones and sticks but also with fire[2], spread from the tropics to the temperate zones in Africa and Eurasia. It was a slow migration: about 30 miles per generation. Why so slow?

Groups that had become too small due to any catastrophe joined a more successful group. When after a catastrophe too many groups joinned, such a successful group became too numerous. Then soon tensions arose: people could not yet live harmonious in a too large group. Then soon a little group of young women, children and men would decided to move to a new territory. Not too far away (maybe some ten days trip) because they needed each other for surviving. We may assume that such a region had already been known because adolescents had to make a long journey as part of their initiation in adult life – upon their safe return, they were able to recall for the remainder of their lives the far away regions and people they had encountered on their journey. Whatever, we fantasize a little here.

Sure is: the settlers of new territories were the first humans who gave the mountains, rivers, lakes, marshes, fruit trees and wild animals their names.

For humans, things exist to the extent we have a name for it.

For our ancestors, as linguistic creatures, those first name-giving settlers were the creators of their tribal territory.

People always had (and still have) the practice of defining a total group as one person (The American for all Americans, The Australian for all Australians) and in a similar way, their offspring spoke of The Big Ancestor.

We have already mentioned dancing / singing as a result of the performances to fill the night-time hours before bedtime around the campfire that kept the predators away. The performances had taken such an important place in their daily routine that they lived their days to it and that they made it beautiful – especially the women – with flowers and feathers. Feierabend.

Of course this is speculation. We can at most refer to the Yanomamö of Napoleon Chagnon, in whom, despite their permanent threat of war, this was still the daily practice evening after evening.

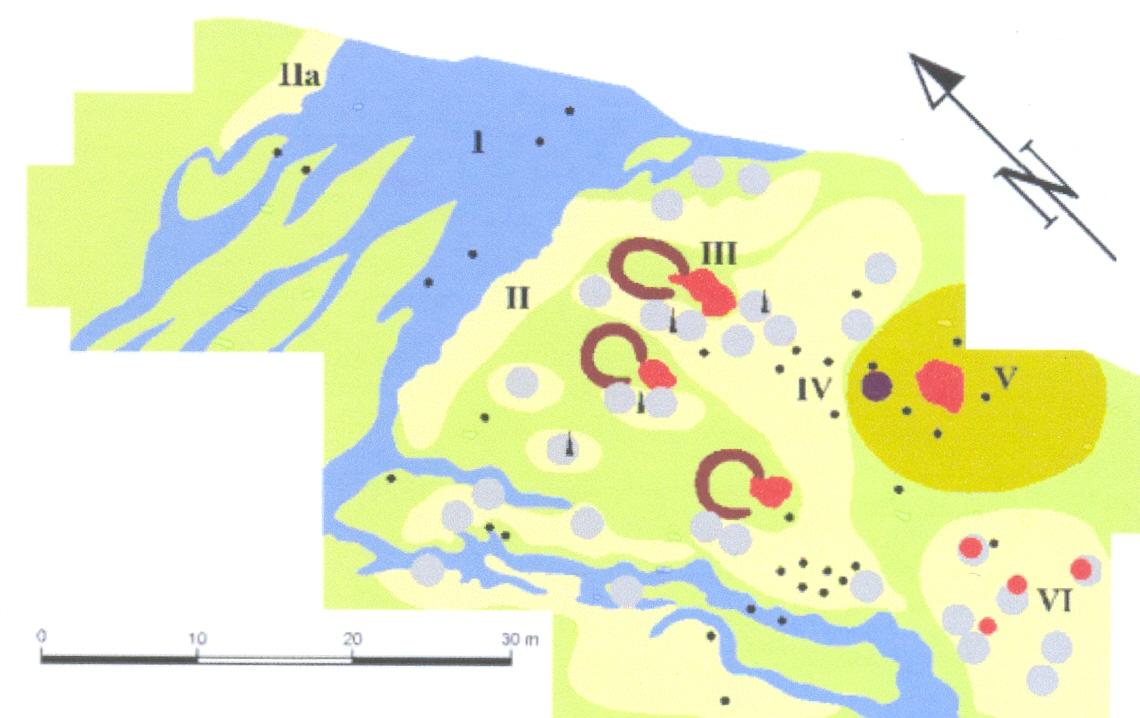

Reconstruction Bilzingsleben camp site of Early Humans, 370.000 years ago

Reconstruction Bilzingsleben camp site of Early Humans, 370.000 years ago

We dare not to speculate exactly when and where this process began. The first hard evidence (in our opinion) of how these humans expressed the experience of their world in danced singing, is Bilzingsleben: an archaeological site in Germany, a H. heidelbergensis campsite from 370.000 years ago (Reinsdorf interglacial). This is the first known place with evidence of a special dance place between 3 huts[3].

The tribal “Big Ancestor” we are talking about here – who was not regarded as a specific person but rather as a reference to the mythical ancestral group – was not a man, nor a woman, nor some kind of animal: it was something all of this.

We need to emphasize here that this tribal Big Ancestor is in no way synonymous with the figure of God as worshipped in today’s main monotheist religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam). The last patriarchal God has been constructed only a few thousand years ago.

Where our atheists claim that God did not create man but that man created God, we may refer to our cultural evolution at this moment of the first people who entered a new tribal area. The little group of young women, children and men who were the first to settle new territories, were the first ones to give the things in that territory their names. For their descendants, the ancestral settler group was personified in ‘epic concentration’, The Big Ancestor.

So God is in essence ourselves – it personified the first little settlers group – and even later thinkers and shamans have always remained aware of this. In the classic Greek-Roman culture of the first century BC, this still may have been the central and deepest mystery of the Mystery Cults and of the Gnosis movement: that God is ourselves. Mystery: in those times it was dangerous knowledge. So dangerous that none of the initiates ever dared to reveal the secret.

Let us take a closer look at Her/Him/It, in the form he still figures as a central force in the creation stories of present-day ‘primitive’ populations such as the Australian Aboriginals.

The creation story of such tribes still tells how in a long-ago Dreamtime[4], the Big Ancestor (never a man or a woman, it was even half-human half animal mythical being) entered the tribe land on a special place and began to journey all through the known world.

Everywhere on his journey She/He/It deposited mountains, lakes and trees and all the special features of the land.

She/He/It also left, in a special place, the little souls who could fly into the wombs of women who passed by that place, the same place to where the souls return after death.

The Big Ancestor could travel through the sky or under the ground.

Once finished with his creation effort, She/He/It departed from the land through a special hole in the ground[5].

Special creations (mountains, trees, animals etc.) were also important Figures in the Story, with special tasks or abilities.

This Story of the creation of their world was so important to them, that they even believed their world would come to an end when they no longer sung/danced their world. And that makes sense: it was a named world for them. And it still is for us – but we are familiar with the fact that the world goes on even when we are never dancing/singing it.

In the dawn of humanity there never was a tribe without a sung/danced Creation Story.

Over thousands of generations of singing/dancing the essence of our world and our community, this practice has become so-to-speak a part of our genome. It lives on within each of us as our religious feeling. We are born with the expectation of experiencing a sung/danced representation of the world and togetherness.

When a baby cries, it will be quiet or even begin to smile when mama sings/dances with the baby in her arms.

This is the base of the religious feeling that remains with us even when we are convinced secularists or atheists. For instance in beauty emotion. It is this ancestral practice of dancing-and-singing the world that makes us “incurably religious” as theologian Dorothee Sölle defined it[6], even though she herself did not see the link.

This instinctive reaction does not just apply to babies. Many grown-ups will feel an urge to dance when hearing dance music.

In a similar way, many people will experience deeply rooted feelings when hearing religious music such as the Matthäus Passion or In Paradisum.

And in fact, the chants by the public in football stadiums do also have the same effect. It tends to bring us in a sort of trance.

Singing (music) is the merger of our cortical ratio (human) and limbic use of voice (animal).

Singing (music) is a return to primitive stage of being human, when we could easily find ourselves in a trance.

In the book Kalahari Hunter / Gatherers by Lee and Devore (1976) we read that the !Kung San attach great value to the trance, but that in order to get into a trance, the women have to dance/sing.

Matthäus Passion and the chants in football stadiums have to do with the desire for trance. Desire to go crazy.

All these common, instinctive reactions to singing and music led me to presume that the sung/danced creation stories by our ancestors played an important role in the group cohesion, which is why this social song/dance mechanism is basically still working even in the nature of western people today.

The creation story as described above evolved over thousands of generations, along with the evolution of the prehistoric economy.

In the creation stories of a few present-day tribes (such as Australian Aborigines) we can still recognize its original form.

- “Religion Explained’ reminds me of “Consciousness Explained” by Daniel Dennett: this book didn’t explain consciousness either. ↑

- this position seems seriously questioned in the recent PNAS article of Roebroeks and Villa (March 2011) “On the earliest evidence for habitual use of fire in Europe”. However, they emphasize that their research concerned (a) the European fire use and (b) the producing of fire: they didn’t question the use of fire by keeping smoldering charcoal obtained from a natural fire. ↑

- Steven Mithen in his book Singing Neanderthals (2006) describes this same excavation, with the “demarcated space for performance (!) … to sing and dance, to tell stories through mime, to entertain and enthrall …” [‘mime’: Mithen has no idea of linguisticness, and even speculates that Neanderthals had not yet language!] ↑

- an important concept of the Aboriginals, but one that is found with ‘primitive’ populations all over the world: it indicates the time of the beginning of being human, when the ancestors felt themselves still being animals, a part of the animal world, not yet linguistic creatures with their existential incertitude as ‘worrying apes’. ↑

- In Australia of the 50’s a whole territory had to be emptied for a nuclear experiment, so emptied from Aboriginal tribes, who were transported with trucks to a new place (it was noticeable that the babies were so well-fed, despite the harshness of their residential area). A later researcher noted that a woman sang for her child, drawing in the sand the Creation route of the Great Ancestor, and it ended with a hole in the ground. ↑

- Dorothee Sölle (1929 – 2003) was a German liberation theologian and writer who coined the term Christofascism. ↑

1.25 The contrast between HGs and AGRs

Four million years or longer our ancestors lived as HGs. The HG-mentality has become part of our genome. Today our babies are still born as HGs. They are even born as NTs: short necks, their windpipes still normally ends in the nasal cavity: they still can simultaneously swallow and breath like normal animals. Until five to eight months: after this time they have become AMM’s.

Also mentally they are born as HGs, expecting to have been born in a HG environment. That is: they expect to be moved, hanging on the mother body, especially a dancing or walking or working mother. They expect smelling her body odor, especially the milky breasts. They expect sounds of people, especially singing. They expect the smell of camp or cooking fire[1]. They especially expect to be loved and cared for.

What they not expect is a cradle in a nursery, stillness and silence. Silence and stillness mean danger and being abandoned. Not to be moved bereaves them from the possibility to lose the surplus energy: they cannot yet move themselves enough to lose surplus energy. Being moved is urgently required. Happily mothers have been born as HGs also, with inherited behavior towards their baby’s, and one can frequently observe AGR mothers and aunts shaking a baby or the pram.

One can see AGRs as frustrated HGs. Frustrated by the change in the inherited HG lifestyle. The last implicated free daily moving from campsite to campsite in a boundless world, in full equality and females in high status. The change into the AGR lifestyle has been forced by over-population, characterized by warfare, a world bounded by tribe territories, an economy of horticulture, a society with male dominance. As horticulturers they lived in longhouses and were no longer ‘noble savages’. The loss of mutual respect was evident primarily in relationship between man and women.

M’buti pygmies, one of the oldest AMM-populations of the world, live as primarily hunters-gatherers but in a weird symbiosis with primitive Bantu farmers in the Ituri forest of Congo. In their past, M’buti men annexed the molima, the rites of the holy flutes and excluded the women from it. But still, women and men remember that this change in gender status is a recent development and once a year they have a ritually reversal of the roles, by mutual consent.

The Bantus however, are farmers and since some 500 years intruders in the Mbuti regions. The Bantus depend for their meat and honey and the labor force of the strong Pygmies, which in turn are eager of the iron knives and other iron things, the tobacco and the palm wine, and even the bananas of the Bantu. A strange and therefore instructive interdependence. Instructive because we can learn from this about the first confrontations of the first farmers with the GH Europe around 4000 BC. And we can learn from the confrontation between the GH mentality with the AGR mentality.

- the predisposition of our tobacco addiction? ↑